It starts with a moment. A pause. A shift in motion, in thought, in breath. The act of preparing matcha is both an embrace and a disruption. There is no simple steeping, no passive waiting while the leaves surrender their essence to the water. There is only presence, movement, and complete immersion. The powder resists at first, clumping together like fragments of thought refusing coherence. It takes effort to break them apart, to bring them into fluidity, but once it happens, the transformation is absolute.

Whisked into suspension, into something greater than its separate pieces, matcha is consumed whole—nothing lost, nothing diluted, nothing discarded. The first sip is velvet, slightly grassy, a thread of umami stretching over the tongue before settling into quiet warmth.

Matcha’s history is a story of transformation, adaptation, and reverence. It is a thread woven through dynasties, monasteries, and ceremonies, carrying the weight of centuries in every sip. Its origins stretch back to the Tang Dynasty in China (618–907), where tea culture was already flourishing.

I step into the heart of ancient China, where the air is thick with the scent of damp earth and the distant hum of traders exchanging goods. The tea leaves, freshly plucked from the dense forests of Yunnan, are carefully laid out, their deep green hues catching the light as steam rises from massive clay vessels. The workers move with practiced precision, steaming the leaves to halt oxidation, preserving their vibrant color and delicate compounds.

Once softened, the leaves are pressed into dense bricks, each one a compacted relic of the harvest, designed for easy transport across vast distances. These bricks are stacked in wooden crates, bound tightly with rope, ready to be carried by merchants traveling along the Silk Road. The journey is long, the bricks exposed to shifting climates—dry deserts, humid valleys, frigid mountain passes. Over time, the tea within them changes, deepening in complexity, developing rich, fermented notes that will later define the aged teas of future dynasties.

In the bustling tea houses of the Song Dynasty (960–1279), these bricks are carefully roasted over open flames, the heat coaxing out their hidden flavors. The hardened edges darken, releasing a smoky aroma that curls into the air. Once cooled, the bricks are ground into a fine powder using stone mills, the rhythmic grinding a steady pulse in the quiet of the tea house. The powder is whisked into hot water, transforming into a frothy, emerald liquid—smooth, rich, and invigorating.

This method, once a necessity for preservation and trade, becomes an art. The powdered tea, once a practical solution, evolves into a revered practice, shaping the way tea is prepared and consumed for centuries to come.

Despite its prominence, powdered tea culture declined in China after the Mongol invasion and the rise of loose-leaf brewing methods. However, its legacy endured in Japan, where it was introduced by Zen monk Myoan Eisai in the late 12th century. Eisai recognized the profound connection between tea and meditation, bringing tea seeds back from China and planting them in Kyoto. His book, Kissa Yojoki (Drinking Tea for Health), documented matcha’s benefits, reinforcing its role not just as a meditative aid but as a vital component of well-being.

Zen monks embraced matcha, integrating it into their practice to sustain long hours of meditation. The act of preparing and drinking matcha became a form of mindfulness, a way to center the mind and body before entering deep contemplation. Over time, matcha spread beyond the monasteries, reaching the warrior class, the aristocracy, and eventually, the broader Japanese culture.

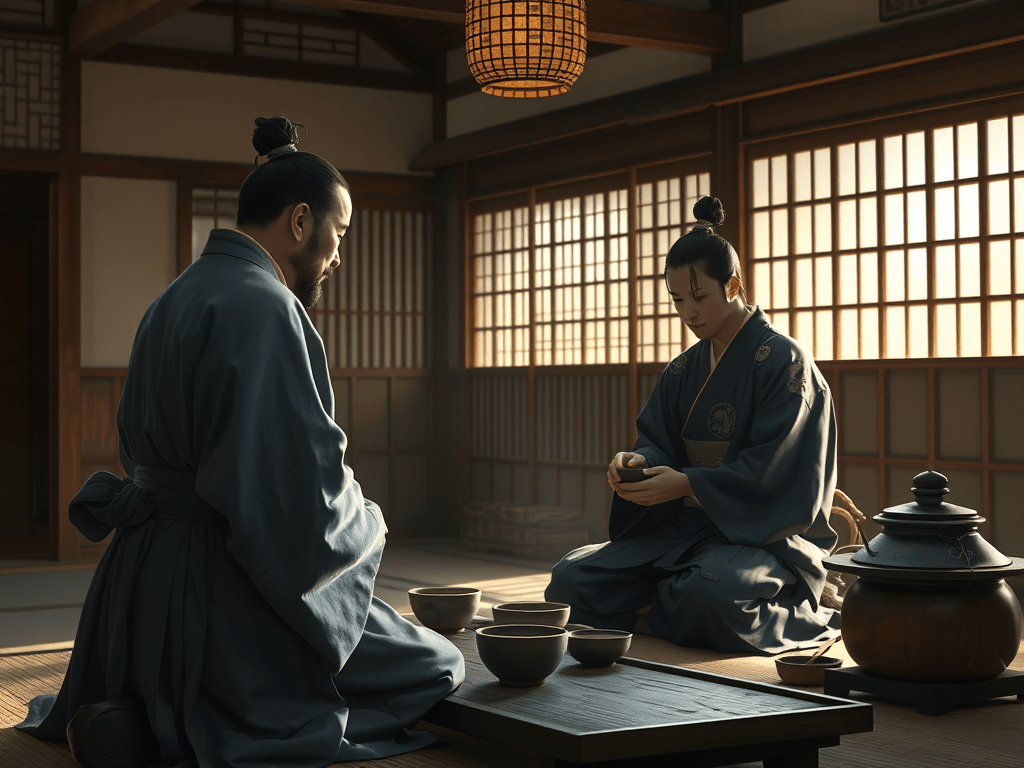

By the Muromachi period, matcha had evolved into something more than a drink—it had become a philosophy. The tea ceremony, chanoyu (Way of Tea), emerged as a structured yet deeply personal experience, shaped by figures like Murata Juko, Takeno Joo, and Sen no Rikyu. Each contributed to the refinement of the ceremony, emphasizing simplicity, harmony, and the beauty of imperfection. Let’s go to feudal Japan together for a moment as if we were the honored guest, a samurai.

The sound of slow footsteps on compacted earth fills the still air, accompanied by the distant trickle of a stream beyond the garden walls. No chatter, no disruption—only the muted hum of wind threading through pine trees, rustling the delicate petals of nearby camellias. Crickets stir within the underbrush, their rhythmic calls blending into the quiet evening.

I step forward along the roji (garden path), its stones worn smooth by the passage of time. The scent of damp earth rises, mingling with the faint aroma of wood smoke drifting from the tea house. Its wooden exterior, darkened with age, holds a richness in its grain beneath the soft glow of a lantern flickering gently at the entrance. The walls bear the weight of tradition, having stood witness to generations of warriors and scholars. Here, the unspoken presence of history lingers—the quiet echoes of conversations long past, the reverence of each footstep taken before mine.

The gate slides open with a quiet rasp. Beyond it, the teishu (tea master) stands, presence commanding yet calm.

His montsuki (formal kimono with family crest) is deep indigo, nearly black beneath the dim lantern light, embroidered subtly with the emblem of his lineage. Over it, his hakama (pleated trousers) flow smoothly, cinched perfectly at his waist. His hair, black as lacquer, is pulled neatly into a topknot, revealing sharp, refined features—angular cheekbones, a gaze both patient and knowing. At his hip, a tanto (small dagger) rests, its lacquered sheath blending into the folds of his garments—a complement to the katana (long sword) that would otherwise be at his side, though tonight, his purpose is different. Without a word, he gestures for me to follow, sleeves shifting slightly with the movement.

Inside, the world slows. The scent of tatami (woven straw mats) fills the air, softened by years of footsteps. Shoji (paper sliding screens) filter soft candlelight into the room, casting shadows against wooden surfaces. The utensils are carefully arranged—chawan (tea bowl), chasen (bamboo whisk), chashaku (bamboo scoop). The tea master moves with precision, every gesture folding into the next, a silent dialogue in motion. He kneels, selecting the chawan with practiced care, fingers grazing its ceramic surface before lifting it into place

I settle into seiza (formal kneeling position), wakizashi (short sword) resting lightly at my side. The kimono drapes fluidly, the obi (wide sash) securing it in practiced refinement. Deep blue—the color of calm waters—the fabric shifts subtly with movement, a silent echo of tradition. The floor beneath me creaks softly as I adjust, the polished wood worn by countless others who have knelt in this very spot.

Steam curls upward as water is poured. The whisk moves in precise, rhythmic strokes, the froth rising, texture fine as silk. The first bowl is presented, resting on polished wood. The chawan, simple yet perfectly imperfect, shaped by the hands of a master potter. I bow in gratitude before lifting it carefully, fingers absorbing the warmth.

The fragrance settles—fresh, grassy, edged with the delicate sweetness of stone-ground tea leaves. The first sip glides smoothly, rolling over the tongue, coating it in layers of bold vegetal depth. Umami lingers, a richness fading into warmth.

The room remains still. The tea master’s gestures remain unbroken, deliberate. The movement of his sleeve, the sound of ceramic meeting wood—it is all calculated, practiced, yet infused with quiet artistry. I lower the chawan, resting it where it had been placed, letting the experience linger as the next step begins.

Every movement, every sip, an act of reverence—a suspended moment where past and present converge.

Now that my moment of chaos and storytelling is appeased, let me share how I prepare my matcha first thing in the morning

My day starts—whenever that is—bringing with it the quiet ritual I have come to depend on. Chaos will have its moment soon enough, but not yet.

I gather my tools, setting each one in its place. No distractions, no wandering thoughts—just the preparation of matcha, a process that steadies the mind before the rest of the world demands attention. One thing I can count on to never change, grounding me at the start of the day.

The matcha is from Japan—the finest I have found. Vibrant green, finely ground, rich in promise. I sit on the floor in front of a lap table, the only practical choice given my mobility issues. Standing for too long, even simply preparing tea, is unpredictable. The last thing I need is to lose balance and spill boiling water, abruptly disrupting the one peaceful moment of my day before it even begins. My water sits beside me, the thermometer waiting—precision matters.

I take my sifter, a simple dollar store find, though I own the proper bamboo furui (tea sieve) as well. One chashaku (bamboo scoop) of matcha is taken from its container, sifted slowly, the fine powder drifting into the bowl in delicate patterns. The motion is unhurried, grounding. As always, I glance up—my service dog and my kitten, well, no longer a kitten, but still “kitten” to me, are watching in silence. Their presence is steady, constant, as if they too understand the significance of this moment.

The chawan (tea bowl) is warmed beforehand—a personal preference—emptied, wiped dry. Once the water reaches its ideal temperature, I pour 60mL—leaning toward the hotter end, knowing how quickly it cools. The whisk moves smoothly, never touching the bottom, angled just right to coax out the finest froth. The rest of the water follows, then honey, the motion uninterrupted.

As tradition dictates, my guests must be acknowledged. Their offering is prepared—dried fish, nothing elaborate, but meaningful in its own way. They invited themselves, after all. If I am going to do something, I want to do it right and honor the tradition when it is something with so much history, even though I am not Japanese.

I pour the matcha into my mug, swishing it gently before taking that first sip. The tea is not dissolved but suspended in the water, each taste bold and unfiltered. The motion is instinctive now, practiced over time.

I remain here, holding onto the moment as long as possible, as my girls enjoy their morning treat alongside me. Once the mug is emptied, the moment fades, and reality resumes its familiar pull.

Later—midday, evening, or whenever the need arises—the process repeats. Almond milk replaces water, and if I’m having a good day, I stand at the counter rather than settling into the floor. I will take the steps, but it won’t take so long, meaning there is no need to seek the floor for safety. The unpredictability of my hours means this ritual happens at different times, always dictated by the ebb and flow of energy. Only in moments of heightened anxiety or the weight of PTSD does the level of detail return to the morning’s precision.

And today, a realization—I’ve been transferring my matcha to a cup all this time. Only now do I understand—I should be drinking straight from the chawan. The irony is amusing. I have every proper tool, yet this fundamental detail eluded me. Years of ritual, yet a single misstep. It changes nothing and yet alters everything. Tomorrow, I will drink from the bowl instead of using an extra dish.

Matcha is not a drink in the passive sense. It is not simply consumed—it is experienced, shaped by movement, by tradition, by necessity. There is effort. There is immersion. There is control. Every step of its preparation serves a purpose, whether rooted in ceremony or in the chaos of a modern kitchen.

Unlike steeped teas that extract essence from the leaves, matcha is whole. There is no straining, no separation—everything remains, suspended in water, taken in completely. This distinction shifts everything. From flavor to texture to the full spectrum of its effects, matcha does not hold back.

It offers a sustained release of energy, sharper focus, steadier nerves. Zen monks understood this centuries ago, relying on matcha to maintain concentration during long hours of meditation, their minds clear yet calm, absent the jittering chaos of harsher stimulants. The compound responsible—L-theanine—works in tandem with caffeine, smoothing the edges, extending clarity without the inevitable crash.

For those with ADHD, matcha offers a rare balance—stimulation without sudden spikes, focus without reckless acceleration. The combination of L-theanine and caffeine modulates brain waves, increasing alpha activity, the same waves present in meditative states. Thought becomes structured without rigidity, energy maintained without volatility.

In anxiety, matcha works differently. The gradual release prevents sharp peaks and valleys, keeping stability intact. There is no overwhelming intensity, no abrupt shifts—just steadiness, presence. The body remains engaged, the mind remains clear.

Chronic migraines, chronic pain—the connections deepen here. The polyphenols within matcha, the antioxidants responsible for its vibrancy, work as natural anti-inflammatories. Blood flow regulation improves, oxidative stress diminishes. But beyond its chemical composition, the ritual itself plays a role. The repetition, the structure, the control—it builds a rhythm that steadies the unpredictable nature of pain.

Physical pain, whether tied to inflammation, injury, or persistent chronic conditions, finds relief in matcha’s properties. Catechins—powerful compounds within green tea—offer natural pain reduction, lowering inflammatory responses that often amplify discomfort. Joint stiffness, muscle tension, headaches—all of these find soft edges when inflammation is controlled. Meanwhile, matcha’s ability to regulate cortisol helps prevent the stress-induced worsening of pain, easing both body and mind in tandem.

Its benefits stretch beyond the immediate. Antioxidants support cardiovascular health, skin integrity, and immune resilience. Matcha carries detoxifying properties, helping the body process oxidative stress more efficiently, reducing the strain placed on vital systems over time.

Beyond its physiological effects, matcha carries a form of psychological weight—a practice of control over the uncontrollable. The act of preparation itself is meditative, a deliberate series of movements that demand focus and presence. In moments of heightened stress or internal discord, the ritual remains steady, unchanging, offering a place to return, to reset. It becomes more than tea. It is an anchor, a moment suspended, a controlled breath in the midst of disorder.

Matcha is not a cure, not an answer in absolute terms. But it is a mechanism, a tool, a practice. It is consumption with intention, absorption without loss. It carries the weight of centuries, the pulse of concentration, the deliberate movement of presence.

And yet, for all its history, for all its benefits, matcha remains just that—tea. A simple act, a fleeting moment, yet one that invites contemplation. How often do we take part in something that forces us to be present? That demands movement, precision, awareness?

Perhaps matcha is not about ritual at all. Perhaps it is about the ability to stop, even for a breath, and consider the depth in something deceptively simple.

What does it take to turn an action into meaning?

What do we allow ourselves to be fully present for?

I would love to hear from you!