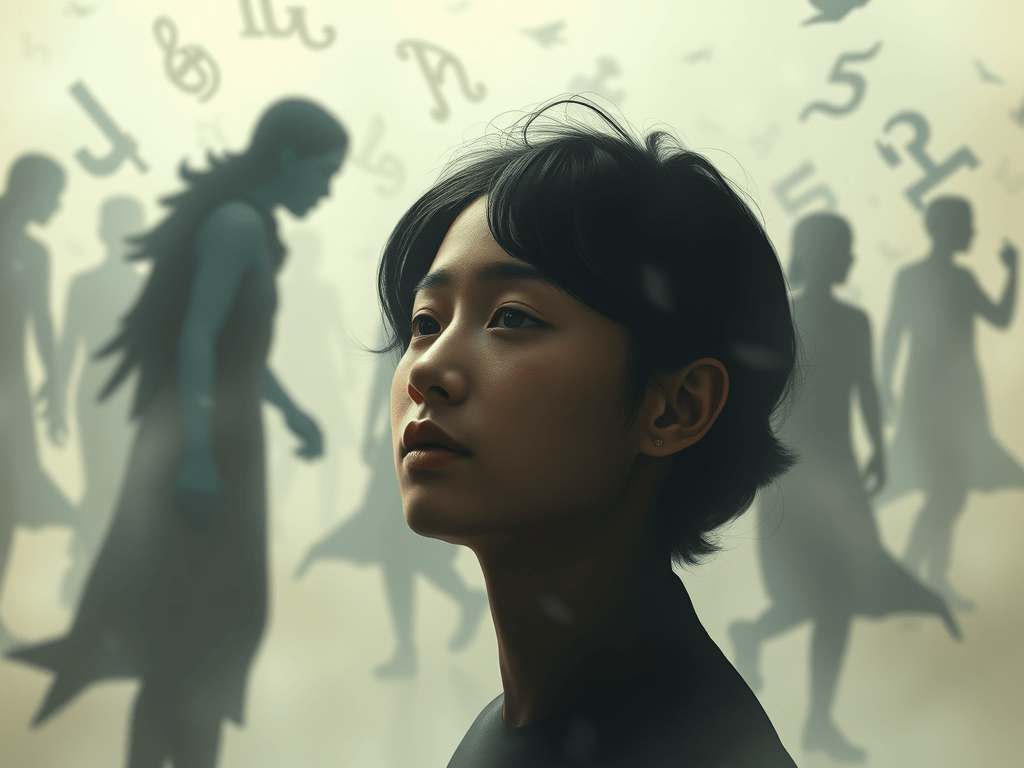

Hyperfocus, Verbal Masking, and the Multilingual Maze of Reclaiming My Voice

Hyperfocus is one of those AuDHD traits that feels like a blessing and a trap at the same time. It allows me to dive deep, to analyze patterns, gather data, explore nuance with breathtaking clarity. And lately, this hyperfocus has been aimed squarely at verbal masking—specifically, how it intertwines with language itself.

The irony? I can speak more than one language now. Maybe two at a level that would probably earn me the label “multilingual.” But that label doesn’t mean what people think it means. It doesn’t mean ease. It doesn’t mean fluency equals authenticity. It doesn’t mean I’ve broken free from masking.

It just means I’ve learned to perform speech in multiple languages.

And that performance? It shifts shape depending on trauma. My first language—English—is the one most loaded with emotional baggage. It’s where my earliest communication breakdowns happened. It’s where I was told to “talk properly,” “use your words,” “stop mumbling,” “stop crying,” “speak up.” It’s the language of corrections, interruptions, discomfort. So now, even when I use English, my mind hesitates. I mask harder. I lose words faster. I freeze more often.

Meanwhile, something remarkable has happened with Plains Cree. I’ve been learning the y-dialect. Each word I become comfortable with slides into my brain like it was always meant to be there. It doesn’t fight me. It doesn’t come attached to emotional static or linguistic guilt. And gradually, it has started to show up first. Cree is becoming my default language—the place my mind switches to instinctively, like a reflex that feels safe. Simply put it is acting like my FIRST language instead of English the one I grew up speaking and am far more fluent in to say the least.

Other languages I’ve studied are following suit, forming a loose ranking behind Cree and well ahead of English. They’re not just languages. They’re access points to expression without trauma. And that has unraveled me in ways I didn’t expect. Because while English used to be my main mode of communication, I now hesitate using it—not because I can’t, but because it costs me something every time I do.

This is where verbal masking gets slippery.

Masking in English feels heavy. It’s tied to years of forced fluency, classroom presentations, phone calls that drained me dry. But masking in other languages feels… different. Softer, but still present. The performance is still there, but it’s built on newer, less painful scripts. I can still tick the boxes for verbal masking in those languages—rehearsing phrases, mimicking native speakers, suppressing my natural cadence. I can feel the performance. It just wears a different costume.

And this confusion of fluency—where my most trauma-free language is one I didn’t grow up speaking—creates dissonance. People hear me speaking Cree or Japanese (at least the basics I know which isn’t much just enough to ask for whatever ingredient I need at my local T&T market or another language and assume I’m “capable,” “comfortable,” “confident.” But capability isn’t comfort. Comfort isn’t authenticity. Sometimes I’m fluent and still masking. Sometimes I’m articulate and still fragmented.

Learning that verbal masking doesn’t vanish with multilingualism was a gut-punch. I thought, “Maybe switching languages would free me.” Instead, I discovered that the mask travels. It adapts. It survives translation. And unless I’m actively unmasking—even in Cree—I’m just swapping the performance tool.

But Cree… Cree is something else.

It’s not just language. It’s reclamation. It’s returning to the roots of identity I wasn’t allowed to embrace as a child. And the fact that my mind now reaches for Cree words first—that my brain says nîsta before me—feels like healing. Not because masking stops entirely, but because it’s the only language where the mask has started to crack.

And that’s what this hyperfocus keeps circling back to.

Verbal masking is not limited to one language. It’s an adaptive strategy our brains build across communication systems. But in those systems where trauma is absent—or where we are actively reclaiming voice—the mask can loosen. It can thin. It can begin to dissolve.

So yes, this new language coming forward first is confusing. Yes, it scrambles conversations. Yes, it adds complexity to identity. But it’s also a sign. That I’m finding ways to speak without cost. That I’m learning what freedom in speech feels like—not in words, but in what they carry. Even if the cost is still extensive to put it mildly.

And maybe, just maybe, it means I’m closer to finding the version of myself who communicates—not to perform—but to exist.

I would love to hear from you!